How Computers Work: The CPU and Memory

|

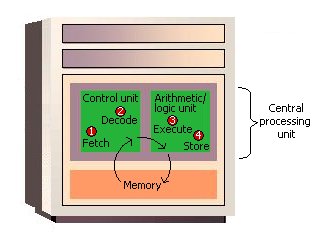

| Figure 2: The Machine Cycle |

Before an instruction can be executed, program instructions and data must be placed into memory from an input device or a secondary storage device (the process is further complicated by the fact that, as we noted earlier, the data will probably make a temporary stop in a register). As Figure 2 shows, once the necessary data and instruction are in memory, the central processing unit performs the following four steps for each instruction:

- The control unit fetches (gets) the instruction from memory.

- The control unit decodes the instruction (decides what it means) and directs that the necessary data be moved from memory to the arithmetic/logic unit. These first two steps together are called instruction time, or I-time.

- The arithmetic/logic unit executes the arithmetic or logical instruction. That is, the ALU is given control and performs the actual operation on the data.

- Thc arithmetic/logic unit stores the result of this operation in memory or in a register. Steps 3 and 4 together are called execution time, or E-time.

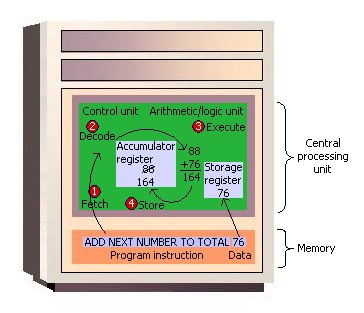

The control unit eventually directs memory to release the result to an output device or a secondary storage device. The combination of I-time and E-time is called the machine cycle. Figure 3 shows an instruction going through the machine cycle.

Each central processing unit has an internal clock that produces pulses at a fixed rate to synchronize all computer operations. A single machine-cycle instruction may be made up of a substantial number of sub-instructions, each of which must take at least one clock cycle. Each type of central processing unit is designed to understand a specific group of instructions called the instruction set. Just as there are many different languages that people understand, so each different type of CPU has an instruction set it understands. Therefore, one CPU-such as the one for a Compaq personal computer-cannot understand the instruction set from another CPU-say, for a Macintosh.

|

| Figure 3: The Machine Cycle in Action |

It is one thing to have instructions and data somewhere in memory and quite another for the control unit to be able to find them. How does it do this?

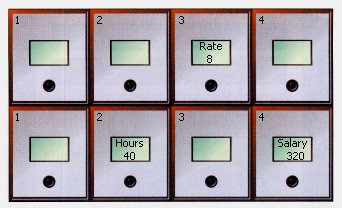

|

| Figure 4: Memory Addresses Like Mailboxes |

Figure 4 shows how a program manipulates data in memory. A payroll program, for example, may give instructions to put the rate of pay in location 3 and the number of hours worked in location 6. To compute the employee's salary, then, instructions tell the computer to multiply the data in location 3 by the data in location 6 and move the result to location 8. The choice of locations is arbitrary - any locations that are not already spoken for can be used. Programmers using programming languages, however, do not have to worry about the actual address numbers, because each data address is referred to by a name. The name is called a symbolic address. In this example, the symbolic address names are Rate, Hours, and Salary.

No comments:

Post a Comment